In less than two weeks time I’ll be journeying to Istanbul yet again. In anticipation of that I wanted to share a wonderful reminiscence of Istanbul from a fellow American, Ernest Gerber,* at the beginning of the 20th century. What you’ll find are Ernest’s striking readings of a number of subjects including Muslim tolerance, Laylat al-qadr, and what I presume to be a Sufi dhikr (rather than Tarawih prayer). But before I begin, a bit of background is in order.

Kiran’s earlier post on The Real Muslims of Lower Manhattan introduced us to the fount of historical information that was gathered and compiled by FDR’s Works Progress Administration (WPA), specifically the Federal Writers’ Project, from 1936 to 1940. The efforts of these writers, however, extended beyond American guide books like our New York City Guide (1939) and New York Panorama (1938). Spread across the country, the writers of the WPA were well positioned to collect the local history and cultural color of many of the America’s oft-overlooked communities and hidden corners. In effect, these writers became the country’s first collective of oral historians. In fact, counted among the hundreds who worked for the WPA was Studs Terkel, who arguably went on to become America’s greatest oral historian.

Kiran and I have searched and continue to search through the rich collection of WPA material for other bits of “Islamicana.” Particularly helpful has been the website maintained by the Library of Congress: American Life Histories: Manuscripts from the Federal Writers’ Project, 1936-1940. The piece that I wish to share now is just one of our discoveries and seemed exceedingly relevant given my own imminent departure to Istanbul. Not only does the Library of Congress provide a rough transcription of the typed interviews, or “life sketches” as they were sometimes called, it also provides digital scans of the original reports.

Allow me at last to share with you some excerpts from one remarkable interview entitled “From Around the World to a Georgia Farm.” Rather than being about some aspect of Islam in America, these words have more to do with an American abroad.

A WPA writer named A. O. Berie met with a Swiss-American neighbor named Ernst Gerber on the latter’s farm just north of the Chattahoochee River in Marietta, Georgia. Locals also called Ernest “Chief” and “Doc” as the writer does in the following life sketch. The interview was conducted on 25 February 1939, but the story that Ernest related covered nearly his entire life.

Berie opens by providing an interesting description of Ernest’s home, part of which reads:

The chest which holds the camp stove also serves as a kitchen table, holding the few dishes and accessories necessary for his simple meals. A few inches above them, and extending nearly across the wall from door to window, is a fine example of Turkish tapestry about 18 inches in width, and immediately above the center of this is a small but excellent water color portraying the murdering of a Sultan’s favorite by the Eunuch and his helpers. (The Chief says she probably waved her handkerchief out the window at some Yankee sailor). Flanking the picture is a pair of wrought brass candlesticks (from Turkey) representing two puff adders. Above each of these is a small framed excerpt, in Arabic, from the Koran. Above these, in the center of the wall is a beautiful prayer rug depicting the mosque of Little St. Sofia. Scattered about the other walls are pictures of Mohammedans in native garb and a couple of fine tapestries. Two small taborets of exquisite inlay workmanship stand near a large oil-cloth covered table which serves as a writing desk and also accommodates the typewriter and a few books and datalogues. (pp. 5-6)

With that our stage is set and Berie then hands over the course of the life sketch directly to Ernest’s own words. And so we learn from Ernest himself that in 1917 he joined the Hospital Corp of the US Navy and then, began in 1920 to visit Istanbul, or Constantinople as he called it. Here is some of what Ernest had to say about a two-year stay in Istanbul that began in early 1924:

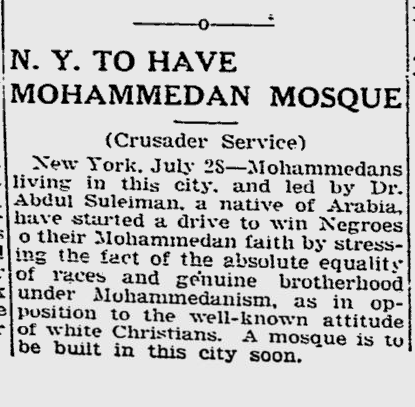

Well, magazines have carried pictures and fine descriptions of the beautiful mosques and palaces in Turkey and nothing I could say would make them more beautiful or interesting. I do say, though, that the so called Christianized people who are always talking about the Turks or Mohammedans being so terribly intolerant, don’t know what they are talking about. They always cite the fact that the beautiful mosaics in the mosque of St. Sofia have been covered with ochre. Well, did you ever see a picture of the Virgin Mary in a Presbyterian or other protestant church? I have been in St. Sofia many times and the thought came to me the first time that if these people were so intolerant, why didn’t they destroy the mosaics? A Yankee boy with a handful of stones could spoil one in a few good throws. And in many cases the only part of the picture covered is the face, and some of these are not even painted over but covered with a gold star. In the same Mosque, on either side of the opening in the hall-way where the faithful enter the inner temple there is a beautiful statue which could have been destroyed with a blow of a hammer; instead they are enclosed in cabinets which are closed up during religious ceremonials, and can be opened to the view of the public at other times.

I had a little adventure in connection with this mosque which might be worth telling about. It was built by The Emperor Justinian I as a Catholic shrine, and is considered the third most holy mosque in Turkey. For that reason it was, at that time at least, closely guarded, and no one was allowed to carry anything inside which might desecrate it. I had tried for nearly a year to get permission to photograph some of the interior but was always refused permission. Well, one day I got acquainted with a shepherd who tended his flock not far from there and after I had visited him many times I told him what I wanted. He finally told me of a way to get in through a narrow opening between the bastions in the rear which was covered with bushes. I sneaked through the opening and not seeing the guard inside I set up my tripod and camera and got two good pictures. Just as I was hurriedly taking down the outfit the guard entered and saw me. He raised his long barreled rifle and was about to drill me when the shepherd rushed in with his hands up, shouting the Arabic word for “immunity.” This was my cue and I dug out my embassy assignment card and handed it to him. Of course he didn’t know what it said but as we were immune from about everything else he thought I hadn’t got a picture yet he finally got friendly and was very courteous from then on.

One day I heard that some prominent man had died and his funeral was to be held at the Mosque of Ayoub [Eyup], on the Golden Horn. Hiking out there I joined the crowd lining the street and waited for the ceremonial procession. I noticed a young man in European clothes standing next to me and spoke to him in Arabic. He answered me in better English than I ever spoke and we immediately became friends. He was highly educated in English and other languages, was a graduate of one of our own famous universities, and was the personal secretary of the Sheik El Islam, the spiritual head of the Church in that part of the empire. He did me many favors during the rest of my stay and helped me to learn more of the Mohammedans and their customs.

Not long after we met, the month of the Ramidan [Ramadan] began. During this period, which begins when the first sickle of the new moon appears after the Vernal Equinox, the faithful fast every day from sunrise to sundown, not even a drop of water reaching their lips. But you’d ought to see them eat and drink between sunset and sunrise! They sure do make up for lost time.

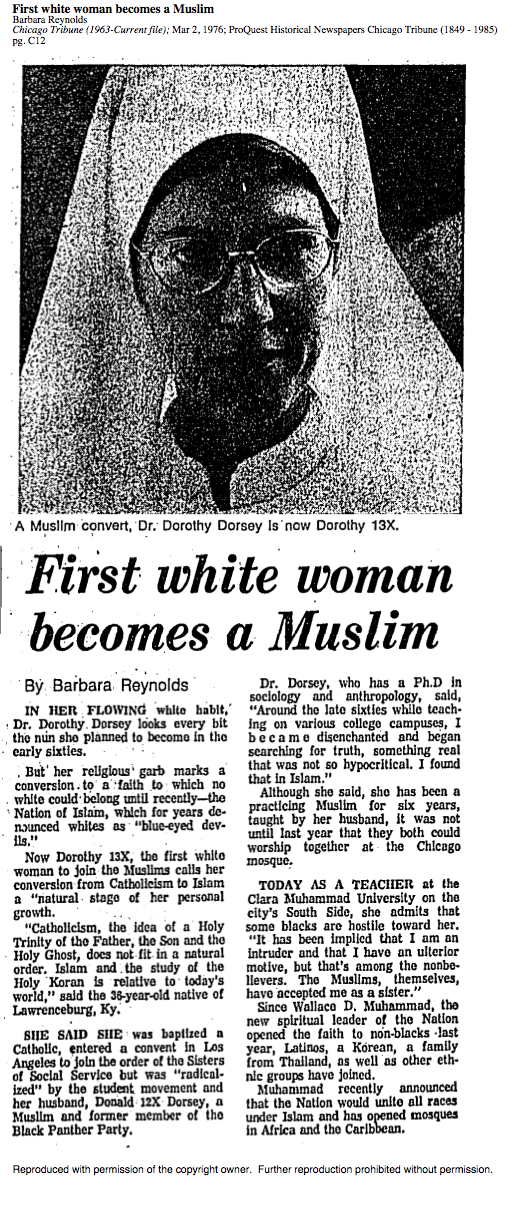

During this month there is one night set apart from the rest and called the Night of Power [Laylat al-qadr]. On this night the spirits are supposed to descend on each worshipper and give him the power to control his body and mind, in fact make them sort of supermen. That is, if they are able to get themselves wrought up to the proper pitch for the reception of the power. I had long wanted to witness one of these gatherings but it seemed I was doomed to disappointment, until I met my new friend and asked him if he could help me out. Well, through his influence with the Sheik I was permitted to attend, clothed in the proper robes and instructed how to act. I must say that I was not greatly impressed with the show. It was not nearly as wild as I had been led to believe; in fact, I’ve seen a lot crazier demonstrations of fanatical emotionalism right here at home at Holy Holler meetings. Very few of the worshipers went into contortions and for the most part it was more of a mass action, the robed figures swaying from side to side and forward and back in unison, me with the rest of them. Maybe its all hooey, but I know from close contact with them that they sure do know how to control their tempers, especially when some fool white man does something that would mean fight right now in any other country.

I sure enjoyed life there and sometimes wished I could have stayed there permanently, but all things must keep moving, so early in 1926 I was ordered to the USS Pittsburg, at Villefranche, France. And here began the long trip which finally landed me back in the States, on the last lap of my journey to Georgia. (pp. 28-30)

The interview continues beyond this and at the very end of the typed report is a brief note scrawled in an expedient cursive hand. It dispassionately states “The subject of this sketch died on Dec. 23-1940” (p. 40) meaning that Ernest Gerber passed away almost two years after having been interviewed.

*In memory of Ernest Gerber (12 January 1883 – 23 December 1940). Thank you Ernest for your memories, sincerity, and honesty and thank you to the men and women of the Federal Writers’ Project for saving so much that would have otherwise been lost.

For those still interested in reading more here is a bonus passage detailing his living accommodations and his observance of firefighting methods in Istanbul/Constantinople:

No, I didn’t find my old sweetheart in that port [Constantinople] but there was plenty of others. Now, I’m not going to spill a lot of hooey about the morals of sailors or make excuses, but what the folks call the immorality of the foreigners is a damn sight better than the same thing in some of the so-called civilized countries. Now, you take a man assigned to shore duty for a long stretch; he would have to spend most of his spare time on the ship, if he didn’t live on shore, and would have to be in at certain hours and put up with a lot of other regulations. Well, he can rent a good room and kitchenette for five dollars a month, get him a good looking girl, and live like a king. Yes, they do everything a wife would do and a lot more than most of them. And let me tell you, they are a darn sight more capable and economical in running a house than the girls here. They have it bred into them in those countries… They mend and press your clothes, buy the groceries, do the cooking, and they sure can cook, and keep the place spotlessly clean. And while you have her she is your woman and nobody else can touch her. Yes, as soon as you’re gone she will be looking for another man, but they got to live just like everyone else.

Since Kemal Attaturk began to reform the country I suppose there have been many changes, and things would be a lot different than when I was there, but my camera retained for me the things as I saw them, and bring back to my mind the incidents that happened at that time. Some things I didn’t photograph pop into my mind once in a while and I was just thinking of the time I saw the fire department go into motion. They didn’t have any waterworks then, just a well here and there, and there seemed to be two crews of firemen, one with red equipment and the other with green. The men wore helmets like the old Roman soldiers and a little short tunic, the rest of the body being bare. Their pump was a sort of barrel-shaped thing which was carried on the shoulders of six men, some extra men being in front and behind them to relieve if the trip was very far, and a number of men carried buckets. There wasn’t any signal system, but a watchman in a tower in some part of the city would cry out when he saw what looked like a fire maybe the word would get around to the firemen after a while. When they heard about a fire they would start running toward the spot and the first crew there might get the job of putting out the fire. If both crews got there about the same time, they would begin bidding on the job of putting out the fire. That’s what happened one day when I was lucky enough to be nearby, and damned if the building didn’t burn down before the owner decided which crew he would hire. (pp. 26-27)