We recently picked up a small booklet from the bookstore at The Ferguson Library called Harlem Treasures: A Unique Guide to Our Neighborhood, Treasures and Sights. While certainly not an antiquarian piece, being published in 2003, the booklet proved interesting for its extensive coverage of Harlem’s religious communities and mention of Malcolm X. Moreover, the publication appears to be a community project having been published by the Alliance for Community Enhancement at Columbia University, Inc.

Within its 114 pages this slim volume also covers subjects such as Harlem’s history, neighborhoods, restaurants and shops. The second chapter on “Religion in Harlem,” however, is indeed the longest. A page therein is dedicated to “Al-Islam” which reads:

Background

Islam is a major world religion founded by the Arabian prophet Mohammed in the seventh century. The central teaching of Islam is that there is one God (Allah) and all Muslims (followers of Islam) are equal before God, regardless of race, class or ethnic background. The five pillars of Islam described in the Qur’an (the holy book of Islam) are the essence of Islamic worship: the profession of faith (shahada), prayer (salat), almsgiving (zakat), fasting (sawm) and pilgrimage (hajj). These rituals constitute the core practices of the Islamic faith. The Muslim community currently numbers more than one billion followers worldwide and is one of the fastest growing religions in the United States, where there are an estimated six million followers.

Mosque Services

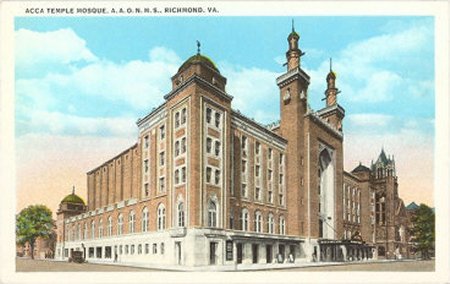

The social and intellectual centers for Muslim communities are mosques, where Muslims worship publicly. Traditionally, mosques were built to face Mecca, in Saudi Arabia, and are dome shaped, with a line marked on the interior wall connecting the center of the dome to the side of the building facing Mecca. Another important feature of mosques is a minaret, or tower, from which the crier (muezzin) calls Muslims to prayer five times a day. Due to the poverty of early Muslims (usually immigrant and African-Americans), most mosques in the United States are housed in buildings originally built for other purposes. U.S. mosques have some distinct characteristics – for example, most do not operate strictly as places of worship but also function as places of public gathering; therefore, many are called Islamic centers. They often house weekend Islamic schools, libraries, conference centers, recreation facilities, residential apartments or community halls.

Typically, everyone in an American Muslim family attends worship. Women usually have a separate space for prayers. (p. 44)

At the end of the book a directory is provided that lists information (relevant in 2003) for two mosques under “Al-Islam” on page 102:

Mosque of the Islamic Brotherhood: 130 W. 113th Street / Imam Talib’Abdur Rashid (212) 662-4100 Sun., 6 P.M.

Mosque Masjid Malcolm Shabazz: 102 W. 116th Street / Imam Izak-El Mu’eed Pasha / (212) 662-2201/2 / Fri. 1 P.M.

The booklet also makes mention of Malcolm X on a number of occasions. Under the Church of God in Christ (COGIC) a section reads:

When Black activist Malcolm X was slain in 1965 and none of Harlem’s major churches would host his funeral, Bishop Childs allowed the service to take place at Faith Temple. In 1973, following the death of Bishop Childs, Bishop Norman Quick was installed as pastor of the Faith Temple Church. He changed the name of the church in 1974 to Childs Memorial Temple Church of God in Christ in honor of its founder. (p. 51)

Then, under “Landmarks of Political or Social Note” the first entry is the Audubon Ballroom:

Audubon Ballroom (3940 Broadway (212) 928-6288) is where Malcolm X was murdered on February 21, 1965. He was both a loved and hated African-American leader. Shortly before his death, he had completed his autobiography, The Autobiography of Malcolm X, which he wrote with the assistance of Alex Haley. It was published in 1965. (p. 73)

Finally, to close this post, under the history section, there is a lengthy, sidebar dedicated to Malcolm X, which is also the only place where the Nation of Islam is ever mentioned. The sidebar reads:

Malcolm X was one of the most influential Black nationalist leaders in the 1950s and 1960s. An outstanding orator and organizer, he was an outspoken critic of American racism. He advocated Black self-defense in the face of racist attacks and urged Black Americans to view the civil rights struggle in the international context of human rights.

Malcolm was born in 1925, in Omaha, Nebraska, to parents Earl and Louis Little, who were active supporters of Marcus Garvey’s Harlem-based Black nationalist organization, the Universal Negro Improvement Association (UNIA). In 1931 Earl Little was found dead – probably the victim of racist violence – and the Little family suffered in response. Malcolm was moved to various foster homes before eventually ending up in Boston to live with his half-sister Ella Collins in 1941.

Over the next five years Malcolm held a wide variety of jobs in both Boston and New York City. Known in the streets of Harlem as “Big Red” and “Detroit Red,” Malcolm entered the underground economy of the ghetto, running numbers, peddling bootleg liquor and selling illegal drugs. Malcolm’s life as a petty criminal caught up with him in 1946 when he was arrested and sentenced to prison for grand larceny and breaking and entering.

While in prison, Malcolm’s brother Reginald introduced him to the Nation of Islam (NOI), a Black nationalist Muslim movement that promoted ideals similar to Garvey’s UNIA, with an added religious dimension that affirmed Black humanity while radically repudiating white supremacy by referring to whites as “devils.” After being paroled from prison in 1952, Malcolm Little joined the NOI and became Malcolm X, with the “X” signifying the unknown true name of his African ancestors who had been enslaved.

Working closely under the NOI leader Elijah Muhammad, Malcolm quickly rose through the NOI hierarchy, and in 1954 he became minister of the NOI’s Harlem Temple No. 7. The decade that followed saw Malcolm establish NOI temples throughout the country and gain notoriety as the national representative of Elijah Muhammad for his fiery speeches denouncing white racism.

By 1964, however, Malcolm had grown disillusioned with the leadership of Elijah Muhammad. That, in addition to internal power struggles as well as possible manipulation by the Federal Bureau of Investigation (FBI), which kept tight surveillance on Malcolm and the NOI, caused an embittered Malcolm to leave the NOI.

He abandoned the racialist teachings of the NOI and established his own Harlem-based Muslim Mosque, Inc. and Organization of Afro-American Unity (OAAU), patterned after the Organization of African Unity – an organization of newly independent African states. Malcolm traveled widely throughout Africa and Asia, and he encouraged Black people in America to view their struggle in the context of the international struggle for human rights. He even announced plans to take the plight of Black Americans before the United Nations.

On February 21, 1965, while speaking at the Audubon Ballroom, Malcolm was assassinated at the young age of 39. Alleged NOI members were convicted for his assassination, but many argue that there exists a compelling case for involvement by others, including the FBI.

A year after his death, his autobiography was published, and it remains one of the most widely read books of the twentieth century that continues to inspire people from all walks of life to this day. (pp. 24-25)

Alliance for Community Engagement. 2003. Harlem Treasures: A Unique Guide to Our Neighborhood, Treasures and Sights. New York, NY: Alliance for Community Engagement at Columbia University, Inc. Co-produced by the Habitat Project.